Since independence, the People’s Action Party (PAP) has won every election by a landslide. Nonetheless, Singaporeans place significant importance on their elections. What do Singaporeans get out of an election whose results never seem to change?

Suraendher Kumarr, Contributor, The Netherlands

The three presidential hopefuls (from L-R): Farid Khan, Salleh Marican, and Halimah Yacob.

It was September last year. I remember being in history class when I heard the news. Out of the five candidates who applied to run for the 2017 presidential election, only one qualified: former member of the People’s Action Party (PAP), Halimah Yacob.

In late 2016, the constitution was amended to ensure that the presidential race in 2017 was exclusively reserved for the Malay community.

This was established on the grounds that Singapore is a multi-ethnic society and therefore required the political representation of its minority groups. Malays constitute 13% of the country’s population, while 74% are Chinese, 9% are Indian, and 3% are ambiguously classified as “others”. Until 2017, there had not been a Malay president since the country’s first President in 1965.

Our first reserved president for the Malay community would also incidentally become our first-ever female president. Nonetheless, she lacked an electoral mandate. Between identity politics and democracy, how did Singaporeans react?

From Silicon Valley with Love…

I remember receiving a phone call from a friend who was studying abroad in Silicon Valley – it must have been 3 am when he called. He expressed his shock and dismay at the outright disqualification of two other seemingly credible candidates for the presidential bid. According to the recent constitutional amendment, a presidential candidate from the private sector is required to be a chief executive of a company with at least $374 million in shareholders’ equity—a significant increase from the previous threshold of $75 million.

One of the disqualified candidates, Salleh Marican, had managed $193 million in shareholder equity, and had his company listed in the Foreign Exchange (FOREX) market. Although Salleh did not meet the new requirement, the constitution also states that the Presidential Elections Committee may choose to qualify a candidate at their discretion. The rigid adherence to what my friend felt was an unreasonable constitutional amendment in the first place, led him to believe that the PAP had “lost touch” with Singaporeans on the ground. He therefore believed that the PAP would suffer some form of backlash for denying Singaporeans a chance to exercise their political right to vote.

Protest against the Reserved Presidency

My friend’s words were prophetic. A few days after Halimah Yacob was inaugurated as the first reserved (and female) president of Singapore, a silent sit-in protest was organized for citizens who wished to express their disagreement with the electoral process. Close to 2000 people graced the event, with many wearing black to show their solidarity to the cause. This was a significant spectacle in Singapore, where freedom of assembly laws are incredibly strict, and protests require a police permit, and are therefore rare. The organizers clarified that the protest was not to criticise Halimah’s presidential capability. Instead, they were critical of the way in which she became President—namely, without an electoral mandate. Did democracy trump identity politics in politically conservative Singapore?

One among 2000 at the silent sit-in protest against the reserved presidency

I largely agreed with the spirit of the protest. In retrospect however, this spirit seemed contradictory for two reasons.

Firstly, why would someone bother about his or her right to vote when the overall results of Singapore elections have continuously proven to be inconsequential to PAP dominance? Since 1963, the PAP has won every single general and presidential election, securing an uninterrupted super-majority in parliament since 1968. The worst performance by the PAP at a general election was in 2011, when it garnered 60 percent of the popular vote and lost a Group Representation Constituency (GRC consists of 5-6 seats instead of 1) for the first time. The PAP however regained its lost ground in the subsequent 2015 snap-General Election, attaining 69.9 percent of the popular vote. Due to Singapore’s first-past-the-post electoral system that it inherited from the British system, the PAP has consistently sustained a disproportionately larger number of seats than its vote share would suggest. From a consequentialist point of view, it appears that our individual right to vote is only significant insofar as it legitimises the incumbent.

Second, a similar situation had already unfolded in 1999 and 2005 but received no such protest. The late SR Nathan, who was formerly associated with the PAP, was “elected” and “re-elected” in both years—when the election committee disqualified all opposition candidates. Given the precedence of an elected president with no mandate, why were close to 2000 people protesting the denial of their political right to vote for their preferred presidential candidate? What set the 2017 reserved presidential election apart from other elections?

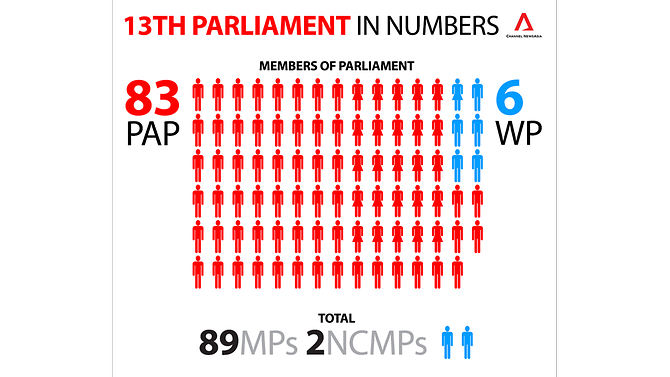

Breakdown of seats allocated to the incumbent PAP (red) and opposition Workers’ Party (blue) after the 2015 General Election.

The role of elections to the common Singaporean

Sociologist Chua Beng Huat argued in his latest book that Singaporeans see elections (mainly parliamentary elections) as the most—if not only—significant way of negotiating their policy interests. In significantly swinging their votes away from the PAP and towards the opposition, the electorate would be signalling their dissatisfaction with the PAP government’s policies. Hence, most Singaporeans are more interested in the way the country is administered (policy) rather than the way power is distributed (politics).

For example, the PAP suffered its largest decline in votes in 2011, when it saw the opposition—the Workers’ Party—make history in becoming the first-ever opposition party to unseat a PAP GRC, even forcing the exit of popular PAP cabinet minister, George Yeo. In response to the shocking results, the PAP stabilised the previously accelerating housing prices, implemented a welfare scheme for the elderly (popular with Singapore’s ageing population), improved public transport, and mitigated the previously high influx of foreign labour. The electorate then proceeded to re-elect the PAP in resounding numbers in the 2015 General Election, causing a drastic 9.9 percent swing of votes back to the PAP.

Some analysts argue that this swing of votes was heavily influenced by two highly emotive events: the death of the first prime minister of Singapore (just a few months before the election); and the country’s 50th anniversary of independence. However, Chua asserts that it is more likely that Singaporeans voted based on their satisfaction with the PAP’s policy shifts. In other words, elections in Singapore serve the purpose of material bargaining with the PAP. Hence, for most Singaporeans (and the PAP government in fact), the extent of votes being swung away from or towards the PAP matters more than the overall result. According to Chua, the overall result is a given for the foreseeable—we will have a PAP government.

The prioritisation of policy over politics can explain the apathy towards the absence of a presidential election in 1999 and 2005. After all, political power is primarily vested in the Prime Minister and his cabinet, while the President’s role is mostly ceremonial. Nonetheless, the President still has significant political powers. They include the ability to exercise veto powers in the cases of detentions without trial, fiscal matters concerning the country’s reserves, and key appointments in the public service. While these powers are politically significant, they do not immediately affect the everyday lives of ordinary Singaporeans, whose first concerns are about getting to work on time, making ends meet, having a secure job, and various other immediate and material concerns. As a result, the thought of “political rights” usually escapes the mind of the common Singaporean.

Front-page of a popular mainstream Singaporean newspaper after the PAP’s big win in the 2015 General Election.

Front-page of a popular mainstream Singaporean newspaper after the PAP’s big win in the 2015 General Election.

Policy vs Politics: a potentially shifting discourse?

Given the more ceremonial role of the President, the presidential election is a low-stakes political process compared to the general election, which is concerned with electing the legislative and executive arms of government. The protest against the 2017 presidential “election”, is therefore significant in our understanding of Singapore society and its political future. The last time a protest saw such a high number of participants was with the Population White Paper protest, which occurred before the 2011 General Election. The protest against the Population White Paper however, was more concerned about material policy issues—especially the government’s target for an even larger population of 6.9 million.

The protest against the reserved presidency therefore suggests a potentially shifting discourse in Singaporean society. Based on alternative media sources, my experience at the protest, banners and placards circulating the internet, and short interviews with fellow Singaporean undergraduates, the general discourse against the reserved presidential election mainly revolved around five issues. 1. The political right to vote in a democracy, 2. The lack of trust the PAP has on Singaporean citizens to choose their leaders, 3. The amendments made to the constitution (Constitutional amendments require the support of a 2/3 majority of parliament. The PAP controls 94% of parliament), 4. The reserved presidency as a means of preventing widely popular opposition figure—the ethnically Chinese Tan Cheng Bock—from competing, and 5. That Halimah Yacob is not an ethnic Malay, but an Indian-Muslim. Apart from the implications on ethnic identity politics in 5, 1-4 suggest the importance of political and democratic rights or liberties.

The protest should also be situated in the context of recent developments in Singaporean politics. Since 2016, there has been a streak of political and civil liberties being curtailed through various constitutional amendments. Some of these include an Administration of Justice (Protection) Act which some deem too repressive, changes to the Films Act which now grants authorities greater powers to enter, search, and seize evidence without a warrant for “serious offences”, and an amendment to the Public Order Act, which now grants the government “special powers” in what is vaguely described as “serious incidents”. More recently, the government is likely to pass new legislation aimed at tackling “fake news”. Many members of civil society organizations in Singapore who argued against the need for legislation were subject to a rather adversarial oral testimony with a select committee formed by the state.

Set against this gamut of illiberal legislation since the PAP’s victory in 2015 , the reserved presidency ostensibly blends in well. However, it is indubitably distinct as it represents what according to Chua is the most significant (if not only) way in which Singaporeans negotiate their interests with the PAP government- the right to vote.

Protestors at the silent sit-in protest.

Protestors at the silent sit-in protest.

The Bigger Picture…

Moreover, Singapore politics should also be regionally contextualised. Across the causeway in Malaysia, the 60-year-old hegemonic party—United Malays National Organization (UMNO)—has been defeated for the very first time since independence. This was despite UMNO’s gerrymandering tactics, members of the public alleging electoral fraud, a contentious fake news bill aimed at curtailing dissent, and several other authoritarian tactics by the former incumbents. The PAP has ruled Singapore for a slightly shorter span: 53 years. Having spent their childhoods as Malaysians, some older Singaporeans felt a sense of pride in Malaysia’s democratic transition, while some others looked to them as an aspiration. It is therefore worth postulating whether the victory of the Malaysian opposition will have any effect in translating Singaporeans’ political frustrations into tangible electoral outcomes.

However, in Singapore there has not been a scandal as controversial as the infamous 1MDB scandal, which involved the former Prime Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak embezzling billions of dollars’ worth of state funds. The recent corruption case involving a Singaporean government-linked company is indeed significant—especially given Singapore’s reputation of being anti-corrupt. However, investigations are still ongoing, and even if it were to incriminate the PAP government, it is nowhere near the scale of the 1MDB scandal in Malaysia. Singaporeans are likely to be divided on whether or not such a charge would warrant a disavowal of the PAP.

Nonetheless, the Malaysian election shows that it is not wise of single-party dominant political regimes to assume that voters’ preferences are perpetually set in stone. The protest against the reserved presidency—a low-stakes political process—suggests that new precedents are possibly being set. This potentially destabilises the PAP’s popularity going into the next general election, a contrastingly high-stakes political process.

While there is little doubt that the PAP will win the next election (most Singaporeans think in terms of the PAP when hypothesising who the next prime minister may be), the extent and direction of the vote swing is less certain. Even more uncertain is whether the loud voices at the protest against the reserved presidency will be heard at the ballot box. Such votes could potentially signify a political awakening among Singaporeans. If so, future elections in Singapore could eventually transcend the role of material bargaining with the ruling incumbents, and start serving the purpose of citizens negotiating their political rights with the state. It would then be up to the ruling party to move with the masses and commit to substantive political liberalisation, or else potentially suffer the same fate as the once hegemonic UMNO.