With his own insight into the field, Jochem van den Boogert gives us his thoughts on decolonising the university. Mr. van den Boogert approaches the issue by answering the questions of how did this issue come about, what can be done, and how can we approach the issue today?

Some thoughts on decolonising the university

Jochem van den Boogert, Gent

Some time ago, I partook in a panel discussion on decolonising Leiden University, organised by BASIS South and Southeast Asia Committee. As the organising committee made it clear they would like to carry on the discussion on the Samudra forum, I offered to write a short essay on my position of decolonising the university. My intention in doing so was twofold. Firstly, this essay is an attempt to formulate my thoughts on the issue as clearly as I am able at this moment. Obviously, over time opinions change and insights grow (sometimes not) and thus this most likely will not be my final stance on the matter. Different perspectives challenge our own thoughts and help us to reconsider what we, at first, took for granted. Hence, my second objective is to invite the other participants in the panel discussion, and of course also members of the audience, to share their thoughts and positions so that we may carry on the discussion that started on the 14th of May.

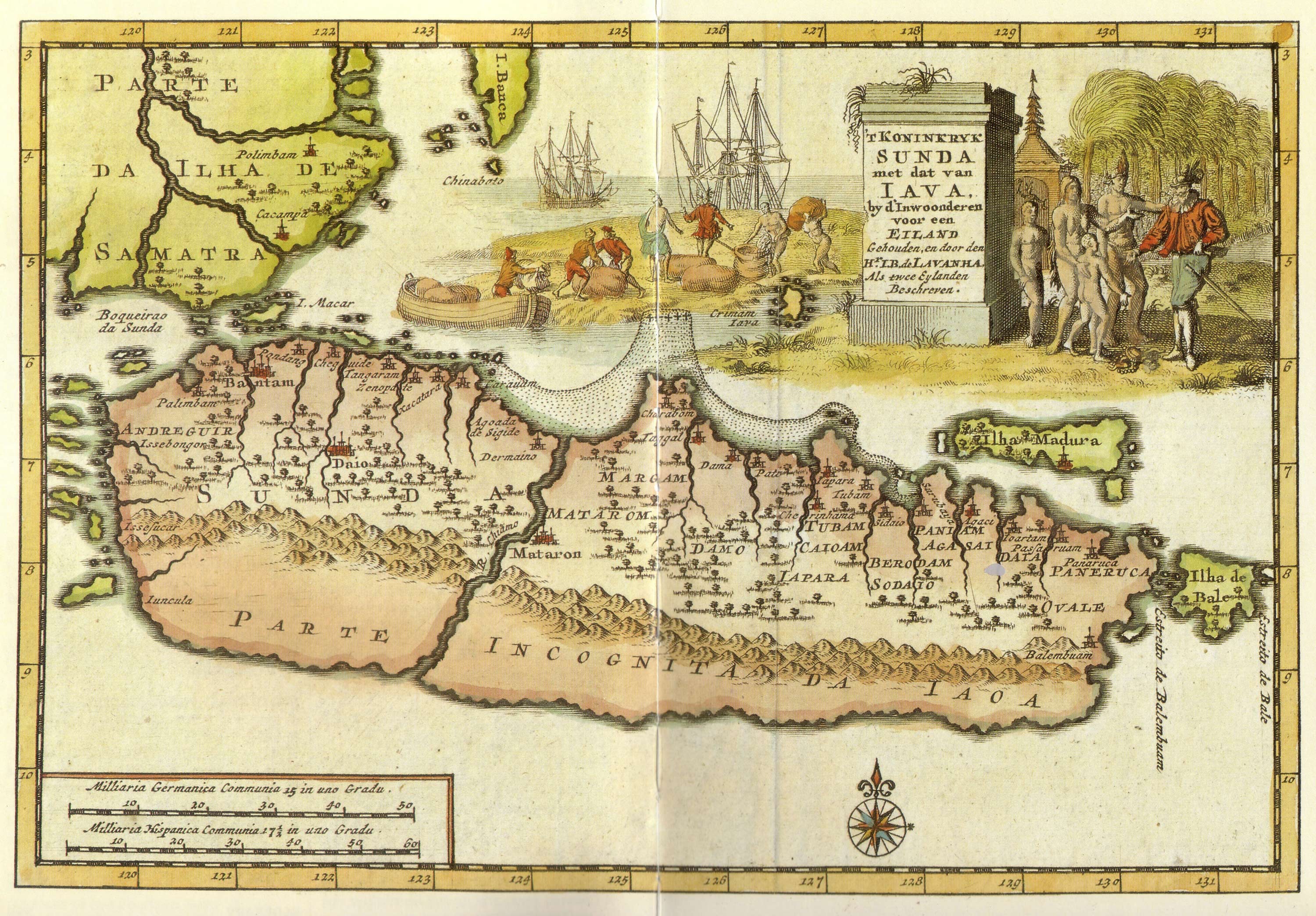

Even though we tend to speak of colonialism as a period in global history that ended with the independence of colonised states, colonialism is anything but a thing of the past. In an obvious sense, it lives on in the economic and political relations between the Global North and South. In a more subtle sense, it still lingers in the institutions of our education, particularly in our contemporary university. However, in order to come to grips with how colonialism still manifests itself today and to get an idea of the magnitude of the task involved in decolonising the university, it is necessary to take a step back and consider the historical phenomenon of colonialism. I will do so here in a cursory manner, loosely drawing on Dutch colonialism in Java. Clearly, much of what can be said about Dutch colonialism also applies to colonialism in general. Moreover, much of what can be said about decolonising Leiden University, can be said about just any university that has a faculty of humanities. Hence, in the text below when I speak about the university, I mean the university as an institute of higher learning in general, and especially their humanities programmes.

Dominant understanding of Colonialism: power and knowledge

The history of Dutch colonialism goes back at least 400 years and its presence was felt, and arguably is still being felt, in regions as diverse and as far apart as South America and Southeast Asia. With regard to Java, colonialism has its roots in the United East India Company (VOC). Although often considered to be the world’s first multinational company, to think of the VOC as merely an economical vehicle would be naive. After all, from its inception political manipulation, brute military force, and exploitation of natural and human resources were key factors to its success. The demise of the VOC at the end of the 18th century CE hardly meant the end of Dutch colonialism in Southeast Asia. Its principal Southeast Asian possessions were reincarnated into the Dutch East Indies in 1800 CE, which, basically, further consolidated the Dutch colonial project in Southeast Asia. Both for the VOC and the Dutch East Indies a sustained subjugation, and at times even eradication, of indigenous populations were part and parcel of their enterprise. This subjugation was not just physical, but also cognitive, epistemological, intellectual. What is the relationship between these two dimensions and how is this relevant for our university?

Let me sketch the currently dominant account of this relationship. At the core of the colonial project, defining and driving it, is a fundamental inequality between coloniser and colonised. The latter is structurally disadvantaged and deprived: subjected to economic exploitation, reduced to an inferior social status, and cut off from political self-determination. A deeply embedded racism sustains this inequality: the coloniser, as an ethnic group or race, is considered to be more evolved and further developed than the colonised, which both “explains” and “justifies” the colonial hegemony. Being familiar with the thoughts of Michel Foucault and Edward Said, most students of BA International Studies will understand the above described relationship in terms of power and knowledge: the colonial discourse, or regime of truth, allows for the colonisers to exert (a threat of) punishment which results in disciplined selves, viz. the colonised subject. Building on this insight, the term Orientalism conveys the systematic nature of the misrepresentation of the non-West, its peoples and cultures, as it is found in Western arts and humanities, and as it is produced in institutions such as the university. This Orientalist knowledge is, thus, that part of the colonial regime of truth that cognitively subjugates the colonised.

The connections between the political and economical subjugation of native populations in the Dutch East Indies and Dutch institutes of higher learning, such as Leiden University, are abundant and revealing. After all, these institutions educated and trained the civil servants for the colonies: here, these civil servants would learn what the culture, religion, laws, and languages were of the populations they would be sent out to govern. Here, the colonial administrators and rulers received the cognitive tools to subjugate the indigenous population. As a case in point, consider how the academic literature of the colonial period asserts that the Javanese are a semi-barbarian race that, although heir to a rich and relatively well-developed Hindu-Buddhist culture, are in dire need of Dutch guidance. This is a pure expression of the aforementioned fundamental inequality, of the racism and discrimination permeating the colonial project. If this is our current understanding of the colonial project and its relationship to knowledge, then what about decolonising the university?

Decolonising the university?

Today, we no longer consider the university to be a site of colonial knowledge production. Obviously, scholars and students alike now consider non-Western cultures to be on par with Western cultures, no longer is there a hierarchy or races and ethnicities. Instead, we direct our intellectual efforts at debunking the Orientalist stereotypes, prejudices and assumptions that once buttressed the systemic inequality between coloniser and colonised. If anything, we are decolonising the university. Or are we? Some critical voices want to go further: they point to the racism, discrimination and (gender) inequality that is present at the university. These are considered structural, part and parcel of institutional mechanisms, and as such, they are considered expressions of the old colonial attitude which still sees the world as one that is divided between “us” (the coloniser) and “them” (the colonised). Subsequently, decolonising the university means breaking the actual practices of racism, discrimination and inequality: a decolonised university is an inclusive university.

Although racism, discrimination and (gender) inequality are undeniably present at many Western universities and although it is undeniably necessary to create an inclusive environment – for students, academic and non-academic staff alike – it would be a mistake to believe that creating such an environment establishes the decolonisation of the university. This mistake, I would argue, has two main causes. Firstly, there is a misconception of what the relationship between, on the one hand, colonialism and, on the other, racism and discrimination – in short “othering” – amounts to. Secondly, there is confusion about the relationship between power and knowledge in the colonial regime of truth.

Two confusions

To start with the first confusion, othering is a dynamic that can be found in all cultures and in many contexts that have nothing to do with colonialism. How many kids are not being bullied for being fat, wearing the “wrong” clothes, or for not being an athlete and so on? What has harassment, sexual and non-sexual, in work situations to do with colonialism? Since when are competing cliques in your local sports club tied to colonialism? How is the discrimination of a Dutchman in Belgium an act of colonialism? As othering is in fact of all times and all cultures, of all layers of society, and basically part and parcel of (all too) many group dynamics, it is not the prerogative of Western colonialism, nor its necessary characteristic. Hence, I would suggest that othering may be a fertile soil for colonialism, but just as the toughest weeds will thrive even on the poorest ground, colonialism can so prosper independently from racist, discriminatory or othering categories and concepts.

Regarding the second confusion, as I already pointed out, it is commonly assumed that the colonial dynamics of subjugation formed the framework within which Orientalist concepts and categories were produced. Subsequently, these are believed to enable, through justification and legitimisation, the actual exertion of colonial power. However, closer inspection shows that this assumption is wrong, which also entails that the above sketched recipe for the decolonisation of the university – viz. debunking stereotypes and prejudices – will not be very productive.

Let’s reconsider the mentioned colonial depiction of the Javanese as a semi-barbarous race. According to the dominant understanding of colonialism, this Orientalist misrepresentation of the Javanese is a wilful imagination that allows for the justification of the colonial project. This, however, completely ignores how the idea, or rather the assessment, of the Javanese as a semi-barbarian race entered the colonial discourse. Ranking the world’s nations and races according to their level of development fits into the West’s endeavour to describe the non-West, which began well before there was any actual colonisation. It is part of a Christian theological – rather than a Western colonial – understanding of the world: the supposed level of mental or civilisational development of the world’s nations was thought to correspond to the religion these adhere to. Animism and ancestor worship indicated a barbarian state of development; polytheism a slightly higher level of mental and civilisational development; monotheism a highly developed civilisation, with Christianity – and Protestantism in particular – on top. Hence within this framework, the Javanese who were thought to combine doctrines from Islam with incompatible doctrines from animism, ancestor worship, Buddhism, and Hinduism could be nothing else but semi-barbarian. The specific structure of the Orientalist misrepresentation of the Javanese as semi-barbarians can be explained by reference to this theological framework. However, this cannot be done by mere reference to a framework of colonial power relations. After all, this cannot tell us why the Javanese would be “othered” by dubbing them specifically semi-barbarians by virtue of their religious condition. Why this specific kind of othering and not another?

Theology and Orientalism

At this point, it is important to stress the overlap of Orientalism with theology. When we look at Western descriptions of non-Western cultures starting from the period of the Renaissance to the 20th century, we can discern a continuum in terms of structuring concepts and a conceptual framework. These concepts and that framework were, from the very beginning of the study of the non-West, theological in nature. One element in that framework is the universality of religion, which, amongst other things, allowed for a description of the Javanese as semi-barbarians. Keep in mind that to the first travellers to Southeast Asia the world was still biblical.[1] According to their bible, god had flooded the earth to wipe out mankind, with the exception of Noah and his kin. After the deluge, Noah and his offspring drifted out to all corners of the world and populated it. However, over time people forgot about this true religion, they strayed into error and started worshipping false gods. Only through the intervention of prophets such as Moses and ultimately the death upon the cross of Jesus Christ would some nations find their way back to the true, original religion – or so Christian theology tells us. Hence, you will find in the early descriptions of Java speculations about which relative of Noah’s could have populated this Island. They also always answer the question as to what the religion of the Javanese is, but never whether the Javanese actually have religion. Hence, the many ritual practices of the Javanese became construed as the expressions of some convoluted (false) religion, as it was just unimaginable that these were anything but expressions of a Javanese religion. Consecutive descriptions of the peoples and cultures of Java built upon these early accounts. Layer upon layer of descriptions result in an unexamined truism: the religion of the Javanese is an ancient syncretism of Islam with pre-Islamic religions.

The above illustrates how a very specific and crucial Orientalist misrepresentation actually has its origin in a Christian theological outlook on and understanding of the world and its peoples, and not in a framework of colonial power relations. Hence, if Christian theology provided the original conceptual framework with which the West made sense of the non-West, then it is also here that we find the origins of Orientalist misrepresentations – and not in the mechanisms of “othering”. How is this very straightforward historical fact relevant to our discussion of the decolonisation of the university? To approach this question, we must first have a look first at the history of the humanities and then at their relationship to Orientalism.

Theology and the humanities

Starting as early as the late 15th, early 16th century CE, the West saw the emergence of the (modern) humanities[2]. While at first firmly embedded in Christian theology, they gradually emancipated themselves from it and came to entail secular disciplines such as history, anthropology, literature, and archeology. In contrast to the common depiction of the Age of Enlightenment as a radical break with the scholasticism of the Middle Ages, it is more apt and fruitful to consider the shift from theological to secular humanities as a gradual process. Additionally, one should think of this process of emancipation, or rather secularisation, as a gradual receding into the background of the specifically theological framework from which theological concepts, such as the concept of religion, and specific theological patterns of thought, such as the universality of religion, received their intelligibility. In other words, many of these theological concepts and patterns of thought have remained present in our current humanities, but the explicitly theological framework within which they actually make sense has become less and less conspicuous.

This proposal has implications for our understanding of the humanities – and in the end also for what it would mean to decolonise the university. Firstly, the humanities are not very scientific. This is the case for two reasons. On the one hand, the aforementioned secularised theological conceptual patterns reappear in our humanities as unexamined truisms. The universality of religion is one obvious example: today, the claim that all cultures have their own religion is still widely accepted as true, but in fact it is neither theoretically nor empirically substantiated. On the other hand, many if not most of the theories formulated within the humanities fail to pass the standards of scientificity. Most are completely ad hoc and it seems little to no effort is invested in formulating hypotheses that can be tested. Hence, theories in the humanities hardly have any explanatory power. Secondly, despite being unscientific, the humanities are nonetheless thought to impart knowledge. An important reason for this is that the humanities appeal to our common sense. However, and this is an important caveat, the humanities dovetail first and foremost with Western common sense, and if, as many have argued, Western culture has to an overwhelmingly large extend been moulded by Christianity, then it is not such a stretch of the imagination to suggest that Christianity has shaped Western common sense.

To summarise, even though many/most theories in the humanities lack a proper scientific foundation, and are in fact based on concepts and patterns of thought that are Christian theological in origin, they are still considered to be fruitful and sensible, as they appeal to Western common sense and hence appear veridical. With this in mind, let’s turn to the question of how the humanities relate to the depiction of non-Western cultures, and, more specifically, to the misrepresentations inherent to colonial knowledge of non-Western culture (aka Orientalism)?

The humanities and Orientalism

There are some Western descriptions of Asian kingdoms that go back to the Middle Ages e.g. from the hand of travelling friars. However, it is safe to state that the truly prolific period of describing and trying to understand the Orient only began with the “discovery” of the spice routes in the late Renaissance. This means that the start of the Western study of Asia (and the non-West in general) coincides with the secularisation of the humanities.

For the purpose of analysis, I will distinguish the humanities from Orientalism: the first signifies the way the West studied itself (its peoples, their societies, cultures, histories, and religions, psychologies, etc.) and the second depicts the way the West studied the non-West (its peoples, their societies, cultures, histories, and religions, psychologies, etc.). Today, of course, the study of both the West and non-West fall within the ambit of the humanities

With this distinction in mind, consider the role the new-found knowledge of non-Western cultures played in the self-understanding of the West. An example of this would be how knowledge of non-Western cultures and religions would be used to reconstruct the history of Europe. A case in point is Ozeray’s Recherches sur Buddou ou Bouddou, Instituteur Religeux de l’Asie Orientale from 1817, in which he discusses and analyses Buddhism in order to better understand the historical origins of the French and European religious condition.

Another example is the discussion on atheism during the Enlightenment period: is there a sovereign god who had created the universe and ruled it, or not? Those arguing in favour pointed out that there exists no civilisation on earth that does not have a religion. Those arguing against would point out that China, known to have a highly developed civilisation, did not have a religion at all, as recent accounts from that part of the world indicated that religion was absent. The discovery – some would say construction – of Confucianism as China’s indigenous religion contributed greatly in settling the matter. Here, Orientalist knowledge of China played an essential role in debates internal to the humanities.

The fact that Orientalism was able to inform the humanities, indicates that both draw from the same repertoire of concepts and theories. This must logically be the case, otherwise the knowledge of either domain must have been unintelligible for the other. That repertoire, it should be obvious, stems from (secularised) Christian theology. Because of their shared ancestry, Orientalism and the humanities share the same conceptual framework, the same assumptions, and the same misrepresentations. The lack of scientificity is shared by both as well. Hence, we should not expect much from the current humanities when it comes to decolonising the university.

Colonialism

How should we think of colonialism in light of what has been argued so far?

I would like to illustrate the points made above by referring to the characterisation of the Javanese as adherents to a syncretist religion, meaning that they combine religious beliefs and practices that actually cannot be combined. Characteristically, a ”syncretist” Javanese person would identify as Muslim – which entails one can only worship one god, viz. Allah – while they would also make offerings to e.g. guardian spirits and the goddess of fertility. Describing such a Javanese person as a “syncretist” Muslim would turn them into hypocrites (they are only Muslims in name) or into fools (they do not understand the requirements of Islam). Such a derogatory stance towards the Javanese was, intellectually speaking, not problematic for the Dutch of the latter half of the 19th century CE – mainly Protestant missionaries and civil servants. After all, this kind of description fitted firmly into their worldview – an explicitly and implicitly, i.e. secularised, theological worldview – where the Javanese were indeed semi-barbarians who were not capable of seeing the error of their ways. Today, many anthropologists of Java consider syncretism a neutral, if not positive, term of description. However, by rejecting its logically pejorative consequences (hypocrisy, foolishness) they are undercutting the theoretical consistency of their account of the religious condition of the “syncretist” Javanese. That is, this kind of anthropological account is just as unscientific, and just as much of a derogatory misrepresentation as the Orientalist account. The core of the misrepresentation lies in framing rituals and traditions – all building blocks of Javanese culture – as elements of a religion. By holding on to this description, even though it has been stripped of its obviously belittling, racist, “othering” connotations, the humanities are actually perpetuating an Orientalist misrepresentation, and preventing a proper understanding of the knowledge that is contained in the traditions of Javanese culture. In fact, this would be an example of how the humanities are perpetuating colonisation. How could this be the case?

I started this essay with the characterisation of colonialism as the subjugation of other people(s), both by force and by complicity of the indigenous elite, with the purpose of economic exploitation. An essential part of this subjugation consists of the colonisers’ description of the colonised people(s) as inferior. Such descriptions serve a legitimising role in the colonisation process. Moreover, such descriptions, especially when disseminated under the colonised population(s), lead to a kind of mental subjugation. Such a colonisation of the mind is also accomplished by force and by complicity, meaning that certain parts of the colonised population adopt these descriptions voluntarily, while they will be forced upon others. The result however is the same: a colonisation of the mind, an appropriation of the coloniser’s misrepresentation of the colonised’s culture. This has perfidious effects, as it cuts the colonised off from his/her own culture, i.e. from their own reservoir of knowledge, of practices, of ways of making a world, of living-together, etc. Over time, this separation from knowledge leads to a situation where non-Western people, educated in the humanities, become incapable of accessing their own (cultural) experiences, let alone make sense of them. In short, it estranges them from their own culture, and forces upon them, what S.N. Balagangadhara has called a “colonial consciousness”. Without further elaborating on this concept, the point that is being raised here is that colonialism is still very much present at the university and that, in particular at the level of the humanities, its effects are still pernicious.

Decolonising the university

Above, I have argued that othering is not the necessary characteristic of colonialism, and that eliminating discrimination and racism from the university – although absolutely necessary – will not lead to a decolonised university. I hope that at this point it has become clear why I believe another kind of effort is necessary to achieve that.

In fact, what we need for a decolonisation of the university is nothing less than a paradigm shift. Paraphrasing Thomas Kuhn, we need a new research model, a new exemplary way to raise and answer those questions that will further our understanding of the different cultures in this world. Our challenge is to lift the humanities to a scientific level which will allow us to come to grips with the different kinds of knowledge that are present in those different cultures. However, in order to establish this new paradigm we need to come to terms with the old one. As I have suggested above, the old paradigm in the humanities consists of secularised theology, which explains the origin of many of its anomalies – representations of a syncretist Javanese Islam being an example of such an anomaly. Our task, then, if we want to contribute to the coming about of this new paradigm, is to locate as many of these anomalies as possible, analyse them and provide better explanations for them. Such explanations would not be ad hoc, would not merely conform to Western common-sense, and would allow for being tested, etc. Taking up this task, I propose, will amount to proper scientific practice. And just as natural sciences are not a “Western endeavour” – i.e. they are not stuck in Western categories, they do not only make sense to Westerners – neither should the humanities be. The process of decolonising the humanities in this sense and hence of decolonising the university has already started.

Jochem van den Boogert

Gent, 23 July 2019

An example of the paradigm-shifting kind of research

where the above essay draws upon: Balagangadhara,

S.N., Esther Bloch, Jakob De Roover. Rethinking

Colonialism and Colonial Consciousness. The Case of Modern India.

https://www.academia.edu/4214196/Rethinking_Colonialism_and_Colonial_Consciousness

[1] This is of course also the case for early Western travellers to every other part of the world.

[2] The subsequent appearance of the social sciences in the latter half of the 17th century CE, falls within this same pattern of emancipation. I will thus not treat the social sciences separately here.